To survive, we transformed.

After independence, Singapore restructured many aspects of its economy, environment, and society. Rivers were dammed to create new reservoirs. Farmland was redeveloped into industrial zones, housing estates, and military training areas. Vulnerable and small, our new nation rapidly built up its institutions and reserves.

Today, as the government redevelops our agriculture and aquaculture spaces of Lim Chu Kang and our surrounding waters into high-tech, resource-efficient, and sustainable agri-food zones, we turn to a similar moment in Singapore’s history nearly four decades ago, when Singapore was undergoing another series of agricultural transformations.

In 1984, after the government decided to phase out pig farming in Singapore, local farmers had to adapt swiftly, seeking new opportunities and livelihoods. By looking at how some of these farmers were able to adapt and successfully reinvent themselves, this article reflects on the continual transformations that Singapore’s farmers and policymakers have undertaken to improve the country’s food security over the years.

Resettlement & Reorganisation

We start this story in the 1970s, shortly after Singapore attained independence. In this period, Singapore witnessed dramatic changes to its physical, economic, and agricultural landscapes, as the government implemented measures to secure and optimise limited natural resources. Water, housing, and the economy were some of the competing national needs that Singapore’s policymakers had to address and balance. To build up our secondary industries, industrial estates sprang up, producing an array of manufactured goods for export. To provide affordable housing for Singaporeans, entire towns planned and built by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) sprouted up in areas like Woodlands, Ang Mo Kio, and Clementi. Large waterways like the Kranji River were dammed to create new water catchment reserves.

Such competing demands, however, also resulted in the shrinkage of local farmland. In one decade, agricultural land in Singapore decreased considerably: from 14,000 hectares in the 1960s to 8,400 hectares in the 1970s. Moreover, to prevent the potential pollution of water supplies by animal waste, pig and poultry farms in newly-created water catchment areas were relocated. From 1974, the government began to resettle pig farmers operating in Lim Chu Kang and Choa Chu Kang to prevent pollution to the Kranji River.

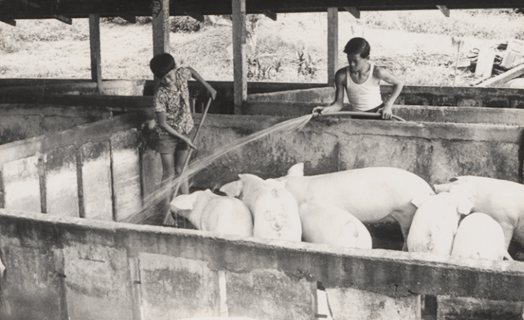

Faced with such circumstances, many small-scale farmers gave up farming completely, taking up the government’s offers of compensation. Some chose to farm less pollutive livestock (like chickens or ducks), while others merged with fellow smallholders to farm pigs at larger, more intensive scales in newly created farming districts like Punggol. With government investment and new technologies, the pork industry in Singapore was rapidly reorganised. Relocated farmers were able to intensify pork production even with reduced land area. By the late 1970s, Singapore was producing almost all the pork it consumed. The era of intensive pig farming had arrived.

Recalibration & Reinvention

Singapore’s development continued at a rapid pace, but by the 1980s, difficult choices had to be made on how to best utilise limited resources. As the country developed, more land was required for needs like housing. Pig farming, however, remained highly pollutive and resource-intensive.

“Taking into account the land constraints in Singapore and looking forward, the government said the land was needed for housing, and pigs were causing land and water pollution,” recalled Dr Ngiam Tong Tau, who was Director of Primary Production at that time. “Cabinet then decided that pigs had no place in Singapore, and we had to phase them out.” Forced to confront these environmental and economic trade-offs, the decision to end pig farming was made in 1984, despite rosy production figures. Policymakers determined it would be more economical in the long run to import all of Singapore’s pork needs, rather than expend limited resources like land, water, and energy to modernise pig farms. Pig farms in Singapore were completely phased out by 1989. In coming decades, Singapore would procure all its pork from overseas sources.

Despite government support to facilitate this transition, such transformations were materially and emotionally difficult for those involved. Yet for some daring, resourceful farmers, the end of pig farming was only the beginning: setting them on new paths of experimentation, innovation, and transformation.

Rather than give up farming entirely, some farmers changed the types of livestock they raised. When pig farming was phased out, Koh Swee Lai (formerly a pig farmer) switched to egg farming. Leveraging the government’s turn to technology-augmented farm production, Koh travelled widely to study egg farming in Japan, England, Denmark and the Netherlands. With government loans and investment, Koh opened Seng Choon Egg Farm at the Sungei Tengah Agrotechnology Park in 1987. The farm was able to continually improve the efficiency of its operations, despite having to confront complications, like complaints from residents in nearby estates about the smells from the poultry; and a major relocation to Lim Chu Kang in 2010, which necessitated a major reinvestment. Continual innovation and investment in new technologies, such as the automation of numerous farm operations, has allowed the farm to remain competitive. In 2019, it was Singapore’s largest egg farm, producing over 600,000 eggs daily, to meet about 12% of local consumption needs.

Similarly, stuck with an oversupply of pigs in his family’s farm in 1984, Mr Lim Hock Chee turned to selling chilled pork from a rented stall at a Savewell Supermarket outlet at Ang Mo Kio. When Savewell later ran into financial difficulties, Mr Lim and his brothers made the momentous decision to take over the management of the entire store. Transiting from pig farming into the retail business, they opened the first Sheng Siong Supermarket in 1985. Through careful planning and prudent sourcing of supplies, the Lims were able to progressively expand the Sheng Siong outlets into a successful local supermarket chain. Today, Sheng Siong is a familiar household name with a comprehensive logistics network serving 66 outlets island-wide; an online shopping platform; and even a television show.

Prime Supermarket, another well-established local supermarket chain, can also trace its beginnings to this uncertain period in the mid-1980s. The Tan family, which owns Prime Supermarket, once operated Tan Chye Huat Farm, the largest pig farm in Singapore, raising over 80,000 pigs annually. The government’s decision to phase out pig farming, however, led the Tans to explore alternative economic sectors to branch out into. In 1985, the Tans opened the first Prime Supermarket, whose modest success encouraged the family to open more outlets across the island. Such experiences gave the Tans the confidence to diversify into other industries, allowing them to grow into Prime Group International (PGI), a large international company with commercial interests in real estate, hospitality, and agriculture.

PGI further expanded into local fish farming in 2018, with the opening of Prime Aqua Sea Farm. Today, Prime has three coastal fish farms along the Pulau Tekong coastline. Under Prime’s management, these farms have started to utilise more advanced technologies – such as solar panels, automated systems, and electric vehicles - to produce more fish with fewer resources. The farm today produces nine species of food-fish for local consumption, and continues to explore more ways to increase production sustainably.

The Present and Future of Singapore farming

Like many sectors, Singapore’s pig farmers have had to adapt to keep up with the transformations the country underwent. Along the way, priorities evolved, and policies had to be reviewed. Difficult decisions had to be made. As we have seen, different farmers developed different strategies to cope with these changes. Some gave up farming entirely, while others switched to raising other livestock, or moved into other industries.

Today, global phenomena such as climate change, geopolitical tensions, and rapid population growth complicate Singapore’s quest for food security. Closer to home, local farms are facing issues of business continuity. Expiring leases, rising agri-input costs, resource constraints, and a lack of successors are some of the challenges today’s farmers have to account for as they plan for the future. Yet the experience of the past decades reminds us that there will always be opportunities for the tenacious, adaptable, and resourceful. To further strengthen its food security, Singapore will continue to diversify its import sources, while also building the capabilities of our local agri-food industry to produce more food sustainably.

Technology and innovation remain some of Singapore’s key enablers, just as they have since the 1970s. The government continues to work closely with farms to adopt the use of new, more efficient technologies. It has also recently introduced a lease mechanism to provide aquaculture farms with greater certainty on their use of the sea space and a longer runway for their investments.

In collaboration with the government, other local farms today are also exploring a multitude of ways to increase their productivity and reduce their resource footprints. Sheng Siong, Prime Group, and Seng Choon Farm, have all continued to explore new techniques and technologies to improve their production capabilities while reducing operating costs. In 2022, SFA also expanded its $60 million Agri-Food Cluster Transformation (ACT) Fund, to support more farms producing a larger variety of food; and to become more productive, climate-resilient, and resource-efficient.

Conclusion: Journeys of Transformation

Independent Singapore’s story has often been told in terms of successful government policy, or its founders’ foresight. But there are other perspectives in the island’s recent past worth learning from, too. External and environmental factors sometimes necessitated that policies be reviewed and trade-offs, made. This brief story of Singapore’s pig farmers after pig farming thus reminds us that there can be opportunities even amid adversity.

Then, confronted with a rapidly changing market environment and an uncertain future, many of Singapore’s pig farmers knuckled down to find new ways forward. They experimented, and ultimately adapted to the circumstances. In this way, their stories reflect the challenges the country itself was facing at the time, as Singapore likewise sought to reimagine and reinvent itself as a global city state. As with other sectors and people of that generation, Singapore’s farmers learned to confront difficulties with a resilient mindset, even as they explored new possibilities and solutions.

About the Author

Choo Ruizhi is a Senior Analyst in the National Security Studies Programme (NSSP) at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He is broadly interested in the environmental histories of Southeast Asia in the twentieth century, and is currently exploring the histories of agricultural animals in newly independent Singapore.